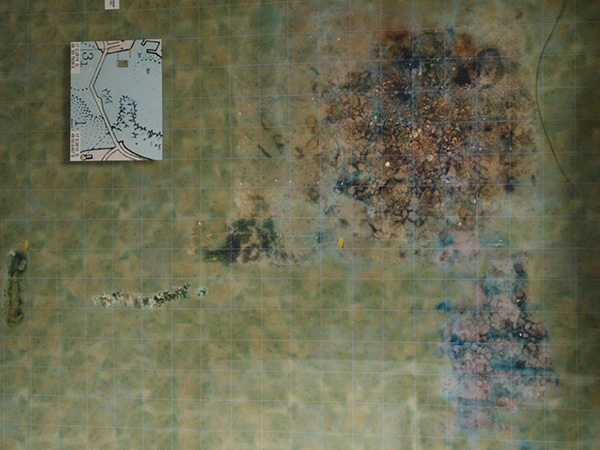

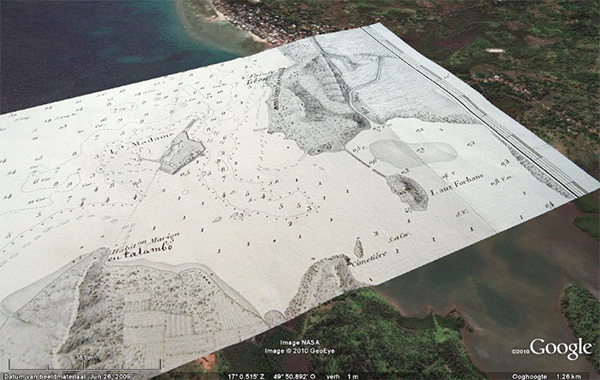

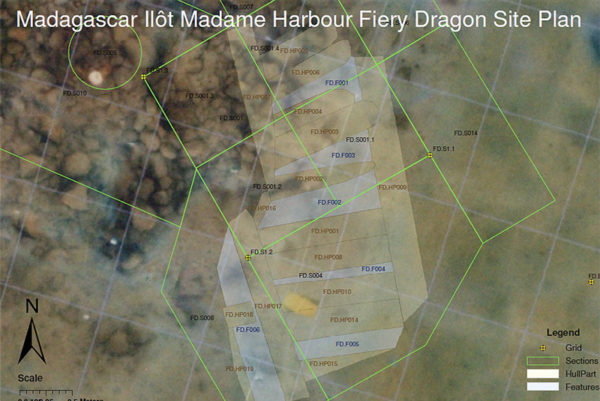

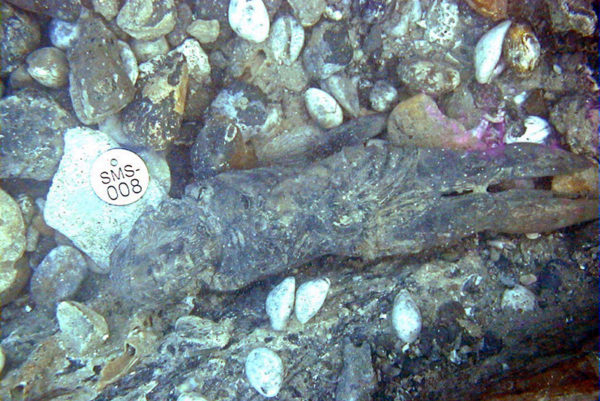

In early 2000, the Center for Historic Shipwreck Preservation embarked on the first of several expeditions to Sainte Marie, Madagascar. During these expeditions, numerous shipwreck sites were discovered, initially identified by the presence of ballast piles, cannons, timbers, and scattered exposed artifacts near Ambodifotatra Bay. The hypothesis was raised that these shipwrecks were those of pirate ships, including the Adventure Galley (1699) commanded by the infamous pirate William Kidd, the Fiery Dragon (1721), the Great Mahomett (1699), the Mocha Frigate (1699), and a “Pilgrim Ship” (1721). Additional shipwreck sites were also located in and around the entrance of Ambodifotatra Bay. Through the analysis of historical evidence, a broad spectrum of artifacts, and comprehensive site data, the research team tentatively identified the Fiery Dragon of pirate Captain William Condon (also known as “Christopher Condent”).

Furthermore, our team conducted initial surveys of a potential early 18th-century tunnel complex on Ile au Forbans in the Bay of Pirates. Ground-penetrating radar detected deep vertical and lateral chambers, along with scattered iron artifacts. It is believed that these tunnels were associated with the pirate settlements of Sainte Marie, serving as strategic and defensive fortifications, as well as possible hiding places for stolen goods.

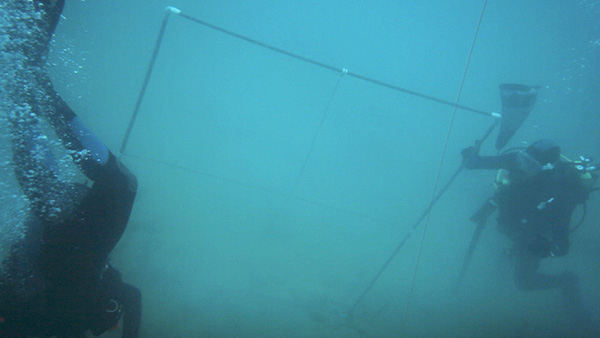

Several subsequent missions have been undertaken to further investigate the Fiery Dragon wreck site, other nearby wrecks, and the tunnel complex on Ile au Forbans. The primary focus has been to gather additional evidence to confirm the nature and identity of these sites. The team conducted a comprehensive study of the area, utilizing a combination of surveys including side-scan sonar, magnetometer, sub-bottom profile, ground-penetrating radar, and surface surveys.

Based on the survey results, the abundance of artifacts, and the complexity of the shipwreck sites, it is expected that future expeditions will yield an exponentially greater amount of material culture and provide further insight into the lives of the pirates at Sainte Marie, Madagascar.

However, future expeditions require careful planning and ongoing financial support. The local museum at Ilot Madame is in need of structural renovations, access to technology, conservation materials, exhibit displays, staffing, and professional training. The Center continues to support these goals by funding museum renovations and artifact upkeep. Through strategic partnerships, the Center aims to garner attention, resources, and sustainable support for the facility.

The Center is committed to a multi-year collaborative project at Sainte Marie. With the support of authorities in Madagascar and the local community on Sainte Marie Island, this project will continue to succeed in researching, recovering, and preserving significant cultural heritage for future generations.

If you are interested in contributing to the continued success of this project, please click here to donate.